“Those who can make you believe absurdities, can make you commit atrocities.” Voltaire

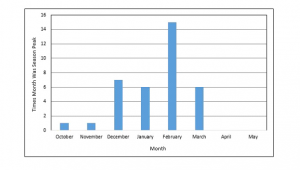

We are in the midst of an annual event – the flu season. While seasonal influenza (flu) viruses infect year-round in the United States, flu viruses are most common during the fall and winter. The exact timing and duration of flu seasons can vary, but influenza activity often begins to increase in October, peak between December and February, and diminish by the end of March. Rarely it can last until May before subsiding. The chart below shows the months in the past which were the seasonal peak for the flu. One third of the time the peak occurred between December and March with February the peak month of all.

A Short History and Description

But first a little background. Most of us are ignorant of what influenza is and how it spread and who it affects the most severely. There are three types of flu viruses: A, B, and C, often referred to as the “common flu”. Type A and B cause the annual influenza epidemics that have up to 20% of the population sniffling, aching, coughing, and running high fevers. Type C also causes flu; however, type C flu symptoms are much less severe. The seasonal flu vaccine was created to try to avert these epidemic. In certain years it has been quite effective, and in others, like 2020, less than 50% effective.

Influenza A viruses are capable of infecting animals, although it is more common for people to suffer the ailments associated with this type of flu. Wild birds commonly act as the hosts for this flu virus. Type A flu virus is constantly changing and is generally responsible for the large flu epidemics. The influenza A2 virus (and other variants of influenza) is spread by people who are already infected. The most common flu hot spots are those surfaces that an infected person has touched and rooms where he has been recently, especially areas where he has been sneezing.

Unlike type A flu viruses, type B flu is found only in humans. Type B flu may cause a less severe reaction than type A flu virus, but occasionally, type B flu can still be extremely harmful. Influenza type B viruses are not classified by subtype and do not cause pandemics. Influenza C viruses are also found in people. They are, however, milder than either type A or B. People generally do not become very ill from the influenza type C viruses. Type C flu viruses do not cause epidemics.

Not all flu is created equal: Some types can make you very ill, while other types cause milder symptoms. Influenza,is a contagious respiratory infection caused by a variety of viruses. Symptoms of flu involve muscle aches and soreness, headache, and fever. Flu viruses enter the body through the mucus membranes of your nose, eyes, or mouth. Every time you touch your hand to one of these areas, you are possibly infecting yourself with a virus. This makes it very important to keep your hands germ-free with frequent and thorough hand washing. Encourage family members to do the same to stay well and prevent flu.

Most people who get the common flu recover completely in one to two weeks, but some people develop serious and potentially life-threatening medical complications, such as pneumonia. Because each flu season is different in length and severity, the number of serious illnesses and deaths that occur each year varies. In the past 30 years, the annual death rate from flu-related causes has ranged from 3,000 to 49,000 deaths per year. Flu-related complications can occur at any age; however, very young children, pregnant women, the elderly, and people with chronic health problems are much more likely to develop serious complications of the flu than are younger, healthier people.

Different strains of the flu virus mutate over time and replace the older strains. The older strains subside as the population develops sufficient immunity to them after exposure. This is sometimes called “herd immunity”. Enough people in the population have developed an immunity to the disease that it can no longer spread. Through vaccine and actual infection this occurs when about 70% of the population has been exposed. This is one reason why it’s important to get a flu shot each year to ensure that your body develops immunity to the most recent strains of the virus.

As determined by the CDC, the viruses in a flu shot and FluMist vaccine can change each year based on international surveillance and scientists’ estimations about which types and strains of the flu will be most potent that year. Previously, all flu vaccines protected against three influenza viruses: one Influenza A (H3N2) virus, one Influenza A (H1N1) virus, and one Influenza B virus. Today, FluMist and some traditional flu shots generally cover up to four strains: two Influenza A viruses and two Influenza B viruses.

There is another more recent strain of flu virus called the “bird” or “avian” flu. Birds can be infected by influenza A viruses and all of its subtypes. Birds are not capable of carrying either type B or C influenza viruses. There are three main subtypes of avian flu, including H5, H7, and H9. The subtypes H5 and H7 are the most deadly, while the H9 subtype is less dangerous. Health care professionals had been very vocal about the strain of avian influenza known as H5N1.

The reason H5N1 has caused so much alarm because it was able to pass from wild birds to poultry and then on to people. While wild birds are commonly immune to the devastating and possibly deadly effects of H5N1. However, the virus has killed more than half of the people infected with it. The risk of avian flu is generally low in most people because the virus does not typically infect humans. Infections have occurred as a result of contact with infected birds. Spread of this infection from human to human has been reported to be extremely rare. People in the United States have less to fear than people who live abroad. Most of the illnesses associated with bird flu have been reported in Asian countries among people who have had close contact with farm birds. Also, people are not able to catch the bird flu virus by eating cooked chicken, turkey, or duck. High temperatures kill the virus.

Corona Virus (COVID-19)

Both COVID-19 and the common flu are viral infections. Both can spread from person to person through droplets — usually from coughing, sneezing or talking. They also have similar symptoms as they both hit your respiratory system and can cause fever, cough, body aches, fatigue and in some severe cases, pneumonia. Neither is a bacterial infection, so they can’t be treated with anti-bacterial medication like antibiotics. Instead, health-care providers try to lessen symptoms, such as reducing fever.

Corona virus broadly refers to a type of virus that’s actually very common around the world. Most corona viruses cause mild to moderate upper-respiratory tract illnesses, like the common cold. According to the Center For Disease Control (CDC), most people get infected with one or more of these viruses at some point in their lives. COVID-19 , however, is a “novel” corona virus. That means it is a new strain of corona virus that wasn’t previously seen in humans. COVID-19 is its formal name.

COVID-19 and the influenza virus, while similar in symptoms, are from totally different families of viruses. Scientists have been studying the flu for years, however, and can work quickly to develop vaccines and treatment in response to mutating strains. We also know that it’s a seasonal thing, and flu outbreaks tend to die down in the spring. But COVID-19 is new and its complete modes of transmission and severity are not completely known. It is known, from the current Chinese outbreak, that for the vast majority (85%) of those infected, the symptoms are mild or almost asymptomatic. That is very good.

Overall according to the U.S. CDC, the death rate of those who have been infected with the influenz A this season is 0.05 per cent. According to research conducted by the Chinese CDC, the case-fatality rate of novel coronavirus is between 1.1% to 2.3%. That estimate is very likely much higher than the real rate as many of those infected had symptoms so mild they never sought medical assistance and are thus unaccounted. The CDC estimate for the common flu is based on a statistical calculation as influenza A and B are not actually tracked, except for those who seek medical assistance.

The good news is that for the overwhelming majority of people who contract COVID-19, it is no worse than the common flu. For those in younger, under 65 age groups, it appears to be very mild and often may be asymptomatic. The bad news is, just because it does not show symptoms, does not mean it is not contagious for at least part of the time one is infected. During that time it can be spread to others. For the age group over 65, especially those with other compromised immune systems or other underlying bronchial issues, it can be much more severe than the common flu. This group should be, and is, receiving the most attentions.

The Swine Flu (H1N1) Pandemic of 2009-2010

it is instructive to compare how a previous influenza pandemic was handled in comparison to the current COVID-19 outbreak. The last pandemic of a new, “novel”, influenza virus occurred in the period from April 2009 through July 2010. The H1N1 virus was not a corona virus, but it’s epidemiology, method of spread and contagion were quite similar.

The 2009 H1N1 influenza virus (referred to as “swine flu”) was first detected in people in the United States in April 2009. It was originally referred to as “swine flu” because laboratory testing showed that its gene segments were similar to influenza viruses that had been most recently identified to circulate among pigs. CDC believes that this virus resulted from reassortment, a process through which two or more influenza viruses can swap genetic information by infecting a single human or animal host. When reassortment occurs, the virus that emerges will have some gene segments from each of the infecting parent viruses and may have different characteristics than either of the parental viruses, just as children may exhibit unique characteristics that are like both of their parents.

In this case, the reassortment appears most likely to have occurred between influenza viruses circulating in North American pig herds and among Eurasian pig herds. Reassortment of influenza viruses can result in abrupt, major changes in influenza viruses, also known as “antigenic shift.” When shift happens, most people have little or no protection against the new influenza virus that results

Health officials reported that the virus had apparently infected people as early as January 2009 in Mexico. The outbreak was first identified in Mexico City on March 18, 2009; immediately after the outbreak was officially announced, Mexico notified the U.S. and World Health Organization, and within days of the outbreak Mexico City was “effectively shut down”. Some countries cancelled flights to Mexico while others halted trade. Calls to close the border to contain the spread were rejected. Mexico already had hundreds of non-lethal cases before the outbreak was officially discovered, and was therefore in the midst of a “silent epidemic”. As a result, Mexico was reporting only the most serious cases which showed more severe signs different from those of normal flu, possibly leading to a skewed initial estimate of the case fatality rate.

The virus was first reported in two U.S. children in March 2009. Another case was reported in Texas in later in the month. Subsequent genetic analysis suggests that it may have started circulating in humans in January 2009. The virus probably first emerged in humans sometime in 2008. It probably had been circulating in Mexico for months but was mistaken as the regular flu until the rash of outbreaks in the spring and the identification of the new H1N1 in April 2009.

Scientists believe the gene-swapping that gave rise to the newly discovered swine flu virus happened 10 or 20 years before, and had spread among pigs for years. But until recently, the virus wasn’t able to spread among people. It acquired that ability only in 2009, when the older triple virus combined again with two other pig viruses that circulated in North American and Eurasian swine.

On April 27, 900 cases of suspected swine flu were reported in Mexico. The World Health Organization (WHO) upgraded the pandemic warning level from 3 to 4 on a six-point scale. Intensive efforts to understand the virus and develop a vaccine begin immediately. The US government advised against travel to Mexico, although research suggested that travel bans are not effective in preventing the virus spread.

In May 20009 the swine flu seemed to be spreading slowly, but it was still progressing quickly enough to justify preparing for a pandemic. However, the WHO delayed declaring a pandemic, partly because there was not enough evidence that the virus was spreading in the general population outside the Americas, where it originated. In Europe no testing of people with flu symptoms occurrred unless they had recently travelled to an affected area in the Americas, or had had close contact with someone who did. As a result, Europe did not detect spread in the general population. These restrictions made the pandemic “invisible” to the monitoring authorities. As concerns mounted, it transpired that many countries were poorly prepared for this scenario and that supplies of H1N1 vaccine could be prepared in time to catch the second wave of the virus spread.

By June 2009 the UK and other countries had changed their rules and started testing people who had flu but no North American contacts. Cases of swine flu wer soon detected. On June 11 the WHO officially declared swine flu to be a pandemic. This was the signal for the vaccine industry to start making pandemic vaccine (paid for by governments), rather than conventional flu vaccine (paid for by ordinary health services).

In July treatment plans were shaken by the discovery of swine flu that was resistant to the antiviral drug Tamiflu and the realisation that the H1N1 vaccine was growing only half as fast as the ordinary flu vaccine. The US decided to use its standard formulation for flu vaccine, so no new regulatory tests would be needed. This allowed it to authorise pandemic vaccine before September, when a renewed wave of the pandemic was expected. But this formulation used a lot of virus, and so reduced the number of doses that could be made.

Researchers discovered that the swine flu virus bound far deeper in the lungs than ordinary flu, possibly explaining why it was sometimes fatal. However, the majority of cases were still mild, and it appeared that many of the people with severe cases had an underlying health problem – although some of these “problems” were no more remarkable than being overweight, pregnant or unborn.

In the southern hemisphere, where it was winter, swine flu apparently replaced the usual seasonal flu. This suggested that the pandemic virus had displaced the two previous seasonal flu strains, as previous pandemics had done. However, after the experience of 1977, when this did not happen, scientists did not rule out the return of H3N2, the old strain of influenza A virus, after the autumn wave of swine flu.

In September 2009 four major vaccine manufacturers reported that their swine flu vaccines worked with only one shot. That was good news, given that vaccine was in short supply despite researchers’ success in finding faster-growing strains. The vaccine’s effectiveness suggested there must be pre-existing cell-mediated immunity, possibly because of similarities between the surface proteins on swine flu and the seasonal H1N1 flu that emerged in 1977.

As autumn arrived in the northern hemisphere, there was a particular worry that swine flu would hybridise with bird flu to create a readily contagious human flu armed with a lethal H5 surface protein. The virus had not become more severe, causing mild disease in most sufferers but making a small number – probably less than 1 per cent – extremely ill.

Vaccination programmes began in the US and Europe in October, but many healthcare workers were reluctant to have the vaccine, even though it was virtually identical to the seasonal vaccines used in previous years, which had a good safety record. Production delays also continued to plague the deployment of vaccine. By October 22, the US had only 27 million doses available, compared with the expected 45 million. Researchers showed that this much vaccine would reduce the number of cases in the second wave by less than 6 per cent – but that was still enough to save 2000 lives.

Six months after swine flu first shot to world attention, in October 2009, President Barack Obama declared the virus a national emergency. By November 19, 2009, doses of vaccine had been administered in over 16 countries. A 2009 review by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) concluded that the 2009 H1N1 vaccine had a safety profile similar to that of seasonal vaccine.

In 2011, a study from the US Flu Vaccine Effectiveness Network estimated the overall effectiveness of all pandemic H1N1 vaccines at 56%. A CDC study released January 2013, estimated that the Pandemic H1N1 vaccine saved roughly 300 lives and prevented about 1 million illnesses in the US. The study concluded that had the vaccination program started 2 weeks earlier, close to 60% more cases could have been prevented. The delay in vaccine administration demonstrated the shortcomings of the world’s capacity for vaccine production, as well as problems with international distribution. Some manufacturers and wealthy countries had concerns regarding liability and regulations, as well as the logistics of transporting, storing, and administering vaccines to be donated to poorer countries.

The vaccine had been successful, but H1N1 had spread massively and for a short time supplanted the older H3N2 strain. However by 2012 the H3N2 strain was again the dominant influenza strain found. This was a big surprise, because in all three of the previous pandemics: 1918 (“Spanish” flu), 1957, and 1968, the new pandemic strain completely replaced the older strain. That had not happened this time. There is now a mixture of H1N1 and H3N2 strains, with the latter being dominant. That’s unfortunate, as H3N2 is a much nastier flu than the swine flu. And beginning in 2011 there was a huge spike in deaths due to flu because of H3N2.

CDC illness and death estimated from April 2009 to April 2010, in the US are as follows:

⦁ Between 43 million and 89 million cases of 2009 H1N1 occurred between April 2009 and April 2010. The mid-level in this range is about 61 million people infected with 2009 H1N1.

⦁ CDC estimated that between 195,000 and 403,000 H1N1-related hospitalizations occurred between April 2009 and April 2010. The mid-level in this range is about 274,000 2009 H1N1-related hospitalizations.

⦁ CDC estimates that between 8,870 and 18,300 2009 H1N1-related deaths occurred between April 2009 and April 2010. The mid-level in this range is about 12,470 2009 H1N1-related deaths.

The pandemic began to taper off in November 2009, and by May 2010, the number of cases was in steep decline. On August 10, 2010, the Director-General of the WHO, Margaret Chan, announced the end of the H1N1 pandemic and announced that the H1N1 influenza event had moved into the post-pandemic period. According to WHO statistics (as of July 2010), the virus had killed more than 18,000 people since it appeared in April 2009; however, they state that the total mortality (including deaths unconfirmed or unreported) from the H1N1 strain is “unquestionably higher”. Critics claimed the WHO had exaggerated the danger, spreading “fear and confusion” rather than “immediate information”. The WHO began an investigation to determine whether it had “frightened people unnecessarily”. A flu follow-up study done in September 2010, found that “the risk of most serious complications was not elevated in adults or children.” In an August 5, 2011 PLoS ONE article, researchers estimated that the 2009 H1N1 global infection rate was 11% to 21%, lower than what was previously expected.

However, by 2012, research showed that as many as 579,000 people could have been killed by the disease, as only those fatalities confirmed by laboratory testing were included in the original number, and meant that many without access to health facilities went uncounted. The majority of these deaths occurred in Africa and Southeast Asia. Experts, including the WHO, have agreed that an estimated 284,500 people were killed by the disease, much higher than the initial death toll.

In June 2012, a model based study was published finding that the number of deaths related to the H1N1 influenza may have been fifteen times higher than the reported laboratory confirmed deaths. According to their findings, 80% of the respiratory and cardiovascular deaths were in people younger than 65 years and 51% occurred in southeast Asia and Africa. The researchers believe that a disproportionate number of pandemic deaths might have occurred in these regions and that their research suggests that efforts to prevent future influenza pandemics needs to effectively target these regions.

Annual influenza epidemics are estimated to affect 5–15% of the global population. Although most cases are mild, these epidemics still cause severe illness in 3–5 million people and 290,000–650,000 deaths worldwide. On average 41,400 people die of influenza-related illnesses each year in the United States, based on data collected between 1979 and 2001. In industrialized countries, severe illness and deaths occur mainly in the high-risk populations of infants, the elderly and chronically ill patients, although the H1N1 flu outbreak (like the 1918 Spanish flu) differs in its tendency to affect younger, healthier people.

A WHO-supported 2013 study estimated that the 2009 global pandemic respiratory mortality was ~10-fold higher than the World Health Organization’s laboratory-confirmed mortality count (18.631). Although the pandemic mortality estimate was similar in magnitude to that of seasonal influenza, a marked shift toward mortality among persons <65 years of age occurred, so that many more life-years were lost. Between 123,000 and 203,000 pandemic respiratory deaths were estimated globally for the last 9 months of 2009. The majority (62–85%) were attributed to persons under 65 years of age. The burden varied greatly among countries. There was an almost 20-fold higher mortality in some countries in the Americas than in Europe. The model attributed 148,000–249,000 respiratory deaths to influenza in an average pre-pandemic season, with only 19% in persons <65 years of age.

A Level Set on Typical Flu Pandemics

With such intense focus on the COVID-19 pandemic, very little attention has been paid to what is a yearly occurrence – the normal flu season of influenza and rhino viruses. The “normal” flu season is marked by an infestation of H1N1 and/or H3N2 influenza viruses. The “swine flu” pandemic was caused by a mutated form of the H1N1 virus. Because of the constant exposure to this virus family over the years, there is a resistance built into our immune systems which helps stem new varieties of the virus. That along with vaccines that have been developed prevent the majority of the population from becoming infected. In a typical year, between 18% – 20% of the population become infected with influenza. The 2018-2019 flu season which began in November 2018 and lasted until early April 2019, peaking in February of 2019.

The flu season was not as severe as the one that came before it, but it set a record of its own, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported. It was the longest in a decade, lasting 21 weeks. Fewer illnesses, hospitalizations and deaths were reported during this period than during previous years brutal flu season, earning the 2018-2019 season an overall severity rating of “moderate,” according to a CDC recap. But the length and trajectory of the flu season—it’s length—was unique, according to the CDC.

Most flu seasons start off with lots of infections from influenza A viruses, which can be more severe and less responsive to vaccination than other subtypes, while generally less-severe influenza B viruses often strike later. But this year two different phases of influenza A activity dominated the season, contributing to its unusual length. H1N1 circulated widely from October to mid-February, then H3N2 picked up from mid-February into the spring. High early-season vaccination rates and a relatively effective annual vaccine help suppress illnesses. In total, the CDC estimated that up to 42.9 million people (13.2% of the population) were infected during the 2018-2019 flu season, 647,000 people were hospitalized and 61,200 died. That’s fairly on par with a typical season, and well below the CDC’s 2017-2018 estimates of 48.8 million illnesses, 959,000 hospitalizations and 79,400 deaths. Pediatric hospitalizations were similar to the previous year’s levels, but there were fewer pediatric deaths: 116 children died from the flu in 2019, compared to 183 in 2018. The mortality rate was approximately .14%. This is an estimate since the number of people infected is a statistical estimate, not a true figure. Typically statistics are only collected for those admitted for medical treatment or die. Those that are untreated must be estimated.

Is the COVID-19 Different or More Dangerous than Influenza

References:

https://www.newscientist.com/article/dn18063-timeline-the-secret-history-of-swine-flu/#ixzz6GuB75ONO

https://www.cdc.gov/h1n1flu/information_h1n1_virus_qa.htm

https://www.webmd.com/cold-and-flu/advanced-reading-types-of-flu-viruses#3